Me reeling in the underway sound velocity profiler, a key piece of equipment on a mapping cruise.

Our team has been underway for four days during which time we have been mapping in a target area outlined by NOAA’s Office of Integrated Ocean and Coastal Mapping (IOCM) located just north of a habitat area of particular concern (HAPC) known as the Florida Middle Grounds. It’s a relatively shallow offshore zone (25-40 meters or 80-130 feet) in the middle of the West Florida Shelf near the part of the state where the panhandle curves into the peninsula – aka ‘The Big Bend.’ This is an important region as it contains a variety of features scattered across the seafloor creating an ideal habitat for fishes and other marine life.

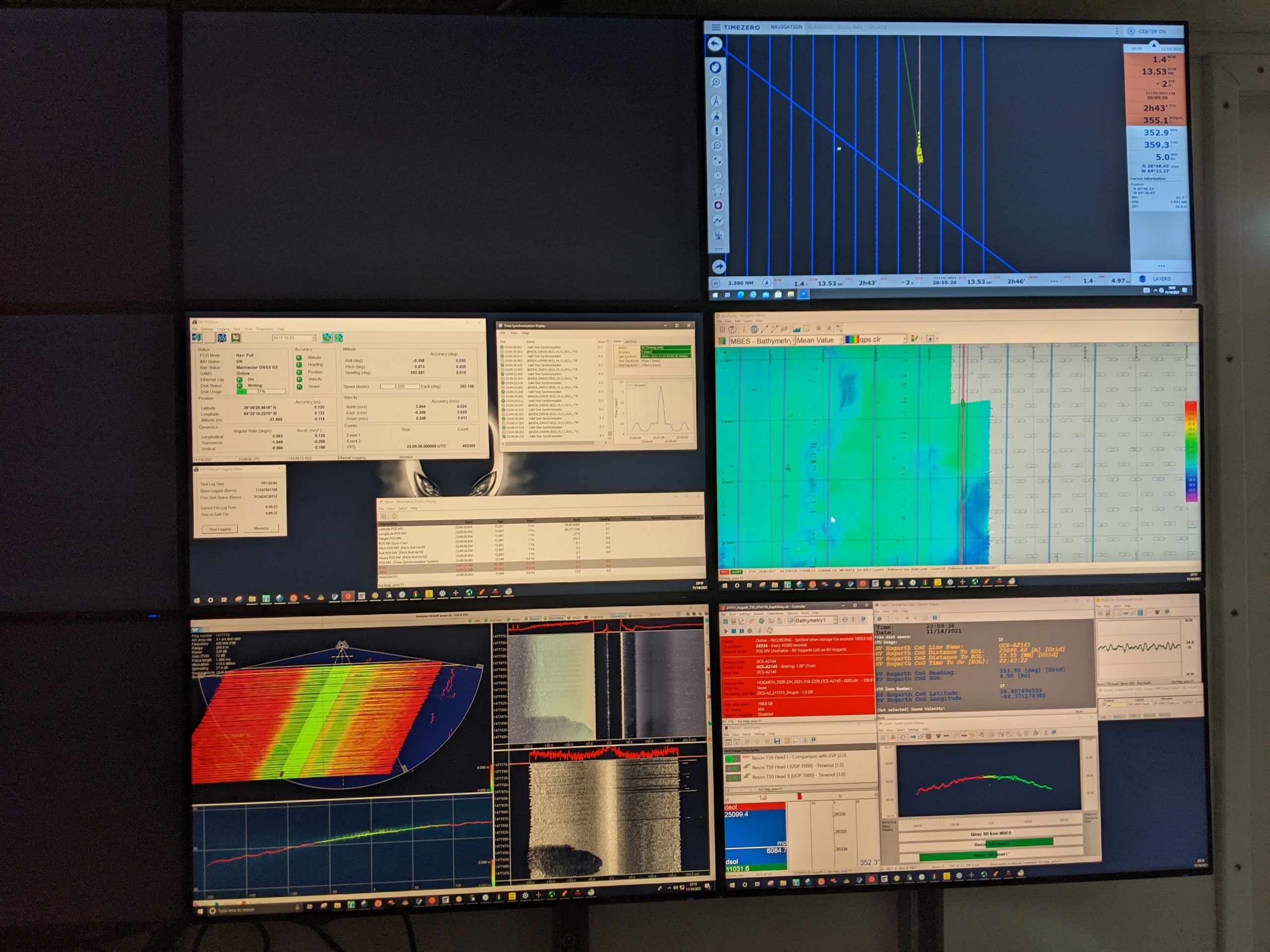

The goal of our work is to create high-resolution bathymetric (or depth) maps of the seafloor using multibeam sonar. The same way satellites use pictures to create maps, we are using sound that emanates from a hull-mounted sonar-head to create images, but it’s a complex task. A team of two is on shift at any one time. One person monitors a wall of screens that shows the images as they are coming in, adjusting the sonar settings, and inputting sound velocity profiles as the water properties change (thereby changing how sound travels through it). All the while the ship cruises back and forth along predetermined lines often referred to as ‘mowing the lawn,’ which makes a lot of sense when you see the perfectly symmetrical lines that the ship is following. As the ship moves up and down the lines, an image slowly begins to unfold of the ocean floor beneath us.

The wall of screens! When we’re on shift, this is what we monitor to make sure the data are coming in properly and all systems are functioning as they should be.

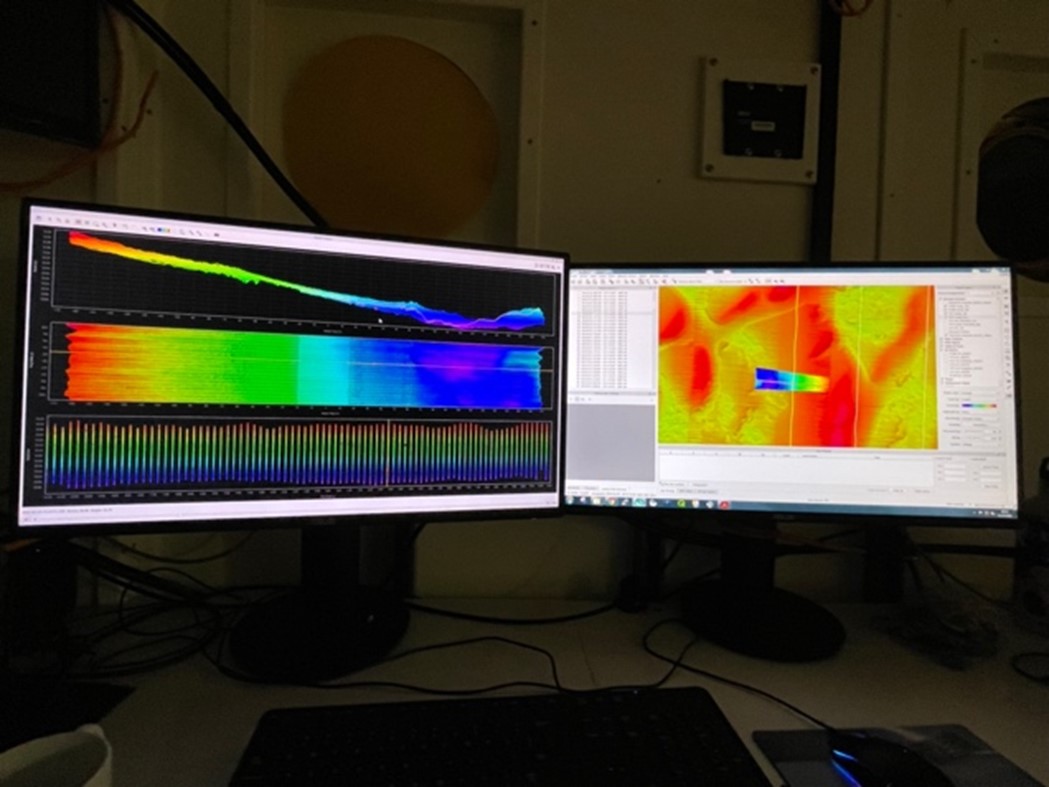

While someone monitors the data acquisition station, another person is typically at the data processing station. They take the data that was just gathered and put it into a software that allows you to edit the data. This process is aptly called ‘killing dots’ because it involves removing individual soundings from the sonar, which appear as dots, when they are deemed to be of poor quality.

The ‘Dot Killing’ station where we edit and process the sonar data into maps.

As mentioned before, the Big Bend region is important for many reasons, and federal entities like NOAA want to explore and understand the area in more detail for tasks such improved maritime safety and better fisheries management, for example. With this goal in mind, we diligently do our work and perhaps if we get lucky we will find some other unexpected goodies along the way (such as a shipwreck!). I also find this work interesting for more personal reasons; my graduate research at USF involves a group of features known as paleoshorelines which mark where sea level used to stand at points in the recent geologic past (e.g. where did Florida’s Gulf coast beaches exist 10,000-12,000 years ago?). It is within the realm of possibility that we uncover new paleoshorelines anytime we map on the West Florida Shelf, and since they have been identified near the Florida Middle Grounds during past surveys, it would be a fun bonus if we found a new one on this cruise!

If you enjoy being on boats and the feeling of being at sea, as well as the added layer of science, then research cruises are always something to look forward to. In between shifts, we hang out on deck and read books or watch movies in the galley, and from time to time we are graced by friendly aquatic visitors like bow-surfing dolphins! There’s also always something new and exciting happening, such as occasionally rough seas that test your balancing skills. Oh, and did I mention – the food onboard is great. For the struggling grad student, three hot meals prepared for you every day is like living in luxury.

Recent Comments