How Do You Age a Fish?

Last week, a handful of the TBS crew attended a two-day workshop on fish ‘ageing,’ generously hosted by Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and led by fish ageing expert and researcher, Kristin Cook. TBS graduate students Kylee Rullo and Alexandra Lee, laboratory technician Daisy Wischmeyer, and program planner Roxann Vistocci learned how to prepare otoliths, cut otoliths, and mount otolith cross sections onto microscope slides before analyzing and ageing. So, what’s an otolith?

An otolith is a fish’s ear bone, a small calcium carbonate structure located within the inner ear of bony fish, and is used as a primary tool for determining a fish’s age. Otoliths exist in three pairs and vary in form. Beyond determining age, otoliths play a crucial role in a fish’s hearing, vibration detection and balance – enabling fish to navigate waters effectively. (NOAA Fisheries, 2025)

Throughout a fish’s life, otoliths grow by adding layers of material around a central core. These layers alternate between opaque and translucent appearances, reflecting changes in growth rate. A wider, opaque layer forms during periods of active feeding, typically in warmer months, as the fish’s diet provides abundant calcium. Conversely, a narrower, translucent layer develops when feeding is reduced, which indicates slower growth. A complete cycle of an opaque and translucent layer represents one year of growth, known as an annulus. (NOAA Fisheries, 2025)

FWC researcher, Kristin Cook (right, front), points to a fish otolith as Kylee (seated), Alexandra (l) and Daisy (r) look on.

Check out otoliths from a red drum (left) and a spotted seatrout (right) in the videos below.

Alexandra references TBS data sheets to fill out microscope slide labels (above). Kristin Cook, shows Alexandra how to mark the core of an otolith (right).

To begin the otolith ageing process, the TBS crew were first shown how to prepare slides. Labels with the fish’s identifying information were placed onto the slides, then small, custom cut pieces of thick, water resistant paper were added. Next, the crew learned how to properly mark the core of the otolith – which is located in a slightly different spot for each species. Otoliths were then positioned onto the pieces of paper and glued in preparation for cutting.

Using an IsoMet® low speed saw, the team learned how to slice otoliths to create three clean cross sections: anterior, core, and posterior. Learning the saw’s weight and speed settings, how to set up and adjust the blades, and how to position the paper with the mounted otolith onto the saw were all part of the training process.

Once three otolith cross sections were achieved, the pieces were carefully removed from the paper using forceps, rinsed in a petri dish of water, and viewed under a small magnifying glass to ensure that a proper core section was obtained. The tiny pieces were then carefully placed onto the fish’s corresponding slide, where they were then affixed with a mounting medium and left to dry in the lab’s fume hood overnight.

Kristin shows Kylee, Alexandra, and Daisy how to operate the saw for cutting otoliths.

A slide tray and slides containing the cross sections of fish otoliths and two uncut otoliths (with cores marked) at the top.

FWC image showing the anterior, core, and posterior sections of a cut fish otolith.

Alexandra, Kylee, and Daisy (l to r) learn from the expert, Kristin Cook (FWC).

On Day 2, once the cross sections were set in the mounting medium, slides were put under the microscope and the TBS team were ready to learn how to age fish. While the process is a bit different for each species, the first step is to locate the first annulus – paired opaque and translucent rings that form during each year of a fish’s life, similar to tree rings. From there, each annuli is counted, with several factors taken into consideration before settling on a final age. These factors can include catch dates, assumed birth dates, how complete the last margin closest to the edge of the otolith might be, and more. Complications may arise in some cases due to human error from the processing stages or a fish simply having difficult-to-identify annuli (NOAA Fisheries, 2025; FWC, 2025). Ageing fish is certainly more of an art than a science! We look forward to practicing and perfecting this skill.

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Kristin Cook and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Fish and Wildlife Research Institute for taking the time and sharing your knowledge and space with us for this two day training. We learned such valuable skills that will allow the TBS team to progress with data analysis – determining ages for our fish catches from an almost-complete year of sample collection.

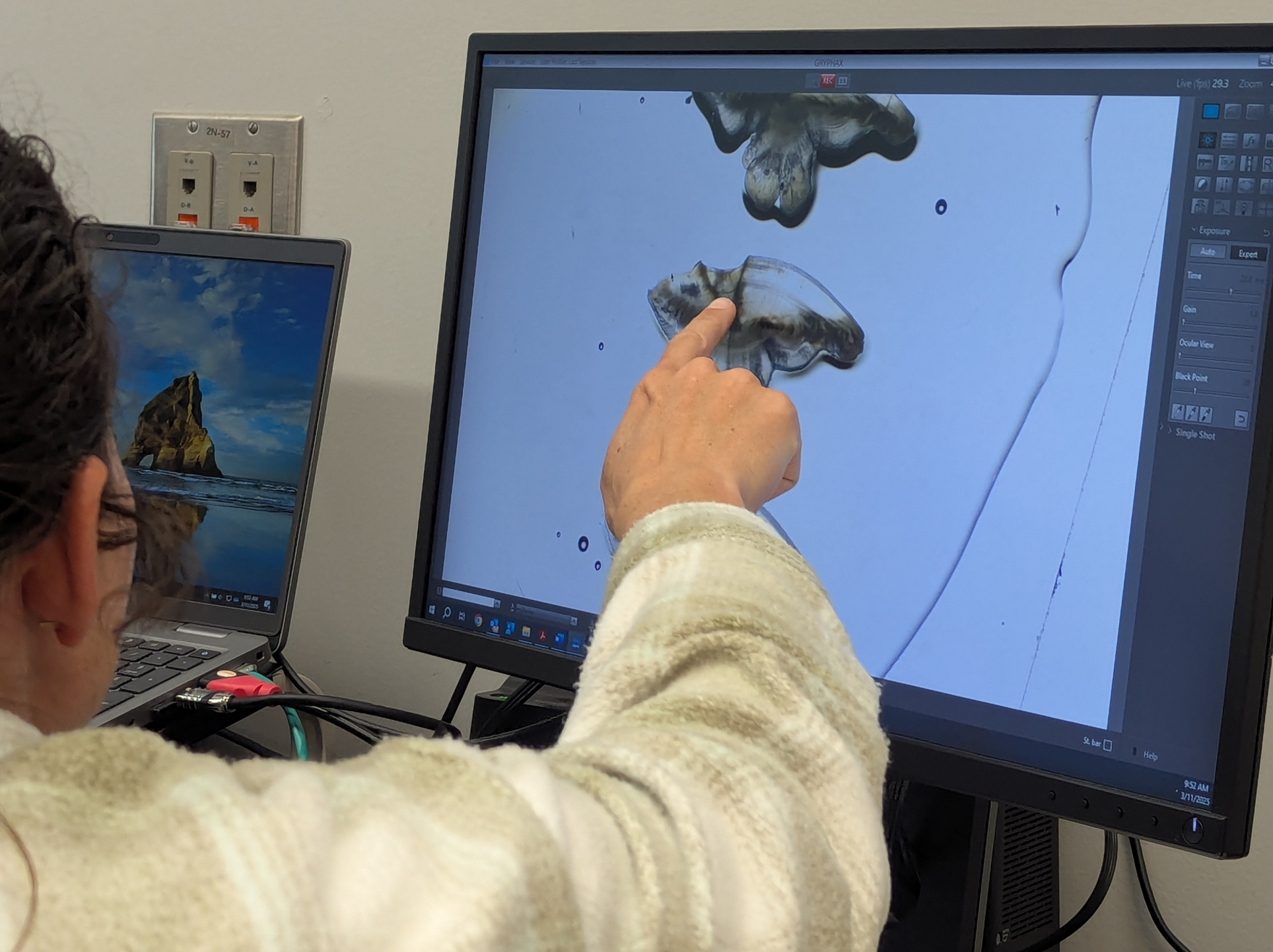

Kylee practices fish ageing, pointing to otolith annuli on a computer screen.